Tgres 0.10.0b - Time Series with Go and PostgreSQL

After nearly two years of hacking, I am tagging this version of Tgres as beta. It is functional and stable enough for people to try out and not feel like they are wasting their time. There is still a lot that could and should be improved, but at this point the most important thing is to get more people to check it out.

What is Tgres?

Tgres is a Go program which can receive time series data via Graphite, Statsd protocols or an http pixel, store it in PostgreSQL, and provide Graphite-like access to the data in a way that is compatible with tools such as Grafana. You could think of it as a drop-in Graphite/Statsd replacement, though I’d rather avoid direct comparison, because the key feature of Tgres is that data is stored in PostgreSQL.

Why PostgreSQL?

The “grand vision” for Tgres begins with the database. Relational databases have the most man-decades of any storage type invested into them, and PostgreSQL is probably the most advanced implementation presently in existence.

If you search for “relational databases and time series” (or some variation thereupon), you will come across the whole gamut of opinions (if not convictions) varying so widely it is but discouraging. This is because time series storage, while simple at first glance, is actually fraught with subtleties and ambiguities that can drive even the most patient of us up the wall.

Avoid Solving the Storage Problem.

Someone once said that “anything is possible when you don’t know what you’re talking about”, and nowhere is it more evident than in data storage. File systems and relational databases trace their origin back to the late 1960s and over half a century later I doubt that any field experts would say “the storage problem is solved”. And so it seems almost foolish to suppose that by throwing together a key-value store and a concensus algorithm or some such it is possible to come up with something better? Instead of re-inventing storage, why not focus on how to structure the data in a way that is compatible with a storage implementation that we know works and scales reliably?

As part of the Tgres project, I thought it’d be interesting to get to the bottom of this. If not bottom, then at least deeper than most people dare to dive. I am not a mathematician or a statistician, nor am I a data scientist, whatever that means, but I think I understand enough about the various subjects involved, including programming, that I can come up with something more than just another off-the-cuff opinion.

And so now I think I can conclude definitively that time series data can be stored in a relational database very efficently, PostgreSQL in particular for its support for arrays. The general approach I described in a series of blogs starting with this one, Tgres uses the technique described in the last one. In my performance tests the Tgres/Postgres combination was so efficient it was possibly outperforming its time-series siblings.

The good news is that as a user you don’t need to think about the complexities of the data layout, Tgres takes care of it. Still I very much wish people would take more time to think about how to organize data in a tried and true solution like PostgreSQL before jumping ship into the murky waters of the “noSQL” ocean, lured by alternative storage sirens, big on promise but shy on delivery, only to drown where no one could come to the rescue.

How else is Tgres different?

Tgres is a single program, a single binary which does everything (one of my favorite things about Go). It supports all of Graphite and Statsd protocols without having to run separate processes, there are no dependencies of any kind other than a PostgreSQL database. No need for Python, Node or a JVM, just the binary, the config file and access to a database.

And since the data is stored in Postgres, virtually all of the features of Postgres are available: from being able to query the data using real SQL with all the latest features, to replication, security, performance, back-ups and whatever else Postgres offers.

Another benefit of data being in a database is that it can be

accessible to any application frameworks in Python, Ruby or whatever

other language as just another database table. For example in Rails it

might be as trivial as class Tv < ActiveRecord::Base; end et voilà,

you have the data points as a model.

It should also be mentioned that Tgres requires no PostgreSQL extensions. This is because optimizing by implementing a custom extension which circumvents the PostgreSQL natural way of handling data means we are solving the storage problem again. PostgreSQL storage is not broken to begin with, no customization is necessary to handle time series.

In addition to being a standalone program, Tgres packages aim to be useful on their own as part of any other Go program. For example it is very easy to equip a Go application with Graphite capabilities by providing it access to a database and using the provided http handler. This also means that you can use a separate Tgres instance dedicated to querying data (perhaps from a downstream Potgres slave).

Some Internals Overview

Internally, Tgres series identification is tag-based. The series are identified by a JSONB field which is a set of key/value pairs indexed using a GIN index. In Go, the JSONB field becomes a serde.Ident. Since the “outside” interface Tgres is presently mimicking is Graphite, which uses dot-separated series identifiers, all idents are made of just one tag “name”, but this will change as we expand the DSL.

Tgres stores data in evenly-spaced series. The conversion from the data as it comes in to its evenly-spaced form happens on-the-fly, using a weighted mean method, and the resulting stored rate is actually correct. This is similar to how RRDTool does it, but different from many other tools which simply discard all points except for last in the same series slot as I explained in this post.

Tgres maintains a (configurable) number of Round-Robin Archives (RRAs) of varying length and resolution for each series, this is an approach similar to RRDTool and Graphite Whisper as well. The conversion to evenly-spaced series happens in the rrd package.

Tgres does not store the original (unevenly spaced) data points. The rationale behind this is that for analytical value you always inevitably have to convert an uneven series to a regular one. The problem of storing the original data points is not a time-seires problem, the main challenge there is the ability to keep up with a massive influx of data, and this is what Hadoop, Cassandra, S3, BigQuery, etc are excellent at.

While Tgres code implements most of the Graphite functions,

complete compatibility with the Graphite DSL is not a goal, and some

functions will probably left uniplemented. In my opinion the Graphite

DSL has a number of shortcomings by design. For example, the series names are not

strings but are syntactically identifiers, i.e. there is no

difference between scale(foo.bar, 10) and scale("foo.bar", 10),

which is problematic in more than one way. The dot-names are

ingrained into the DSL, and lots of functions take arguments denoting

position within the dot-names, but they seem unnecessary. For

example there is averageSeriesWithWildcards and

sumSeriesWithWildcards, while it would be cleaner to have some kind

of a wildcard() function which can be passed into average() or

sum(). Another example is that Graphite does not support chaining (but Tgres already

does), e.g. scale(average("foo.*"), 10) might be better as

average("foo.*").scale(10). There are many more similar small

grievances I have with the DSL, and in the end I think that the DSL ought to be

revamped to be more like a real language (or perhaps just be a

language, e.g. Go itself), exactly how hasn’t been crystalized just

yet.

Tgres also aims to be a useful time-series processing Golang package (or a set of packages). This means that in Go the code also needs to be clean and readable, and that there ought to be a conceptual correspondence between the DSL and how one might to something at the lower level in Go. Again, the vision here is still blurry, and more thinking is required.

For Statsd functionality, the network protocol is supported by the tgres/statsd package while the aggregation is done by the tgres/aggregator. In addition, there is also support for “paced metrics” which let you aggregate data before it is passed on to the Tgres receiver and becomes a data point, which is useful in situations where you have some kind of an iteration that would otherwise generate millions of measurements per second.

The finest resolution for Tgres is a millisecond. Nanoseconds seems too small to be practical, though it shouldn’t be too hard to change it, as internally Tgres uses native Go types for time and duration - the milliseconds are the integers in the database.

When the Data points are received via the network, the job of parsing the network stuff is done by the code in the tgres/daemon package with some help from tgres/http and tgres/statsd, as well as potentially others (e.g. Python pickle decoding).

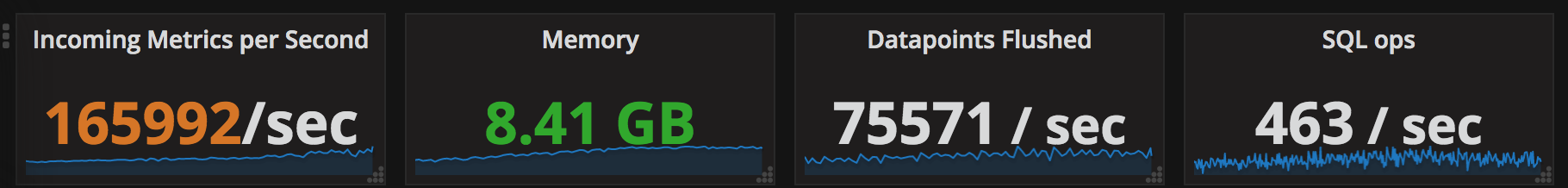

Once received and correctly parsed, they are passed on to the tgres/receiver. The receiver’s job is to check whether this series ident is known to us by checking the cache or that it needs to be loaded from the database or created. Once the appropriate series is found, the receiver updates the in-memory cache of the RRAs for the series (which causes the data points to be evenly spaced) as well as periodically flushes data points to the data base. The receiver also controls the aggregator of statsd metrics.

The database interface code is in the tgres/serde package which supports PostgreSQL or an in-memory database (useful in situations where persistence is not required or during testing).

When Tgres is queried for data, it loads it from the database into a variety of implementations of the Series interface in the tgres/series package as controlled by the tgres/dsl responsible for figuring out what is asked of it in the query.

In addition to all of the above, Tgres supports clustering, though this is highly experimental at this point. The idea is that a cluster of Tgres instances (all backed by the same database, at least for now) would split the series amongst themselves and forward data points to the node which is responsible for a particular series. The nodes are placed behind a load-balancer of some kind, and with this set up nodes can go in and out of the cluster without any overall downtime for maximum availability. The clustering logic lives in tgres/cluster.

This is an overly simplistic overview which hopefully conveys that there are a lot of pieces to Tgres.

Future

In addition to a new/better DSL, there are lots of interesting ideas, and if you have any please chime in on Github.

One thing that is missing in the telemetry world is encryption, authentication and access control so that tools like Tgres could be used to store health data securely.

A useful feature might be interoperability with big data tools to store the original data points and perhaps provide means for pulling them out of BigQuery or whatever and replay them into series - this way we could change the resolution to anything at will.

Or little details like a series alias - so that a series could be renamed. The way this would work is you rename a series while keeping its old ident as an alias, then take your time to make sure all the agents send data under the new name, at which point the alias can go away.

Lots can also be done on the scalability front with improved clustering, sharding, etc.

We Could Use Your Help

Last but not least, this is an Open Source project. It works best when people who share the vision also contribute to the project, and this is where you come in. If you’re interested in learning more about time series and databases, please check it out and feel free to contribute in any way you can!